Rare Earths in Ukraine? No, Only Scorched Earth.

By Javier Blas, Bloomberg, February 19, 2025

ICLC Editor’s Note: It should not come as a surprise that the jewish communitarian branch, in the U.S.A., would deceive both the White House and the American people in order to advance its dystopian agendas to install a world government that is headquartered in Israel.

What Ukraine has is scorched earth; what it doesn’t have is rare earths. Surprisingly, many people — not least, US President Donald Trump — seem convinced the country has a rich mineral endowment. It’s a folly.

It’s not the first time that Washington has gotten its geology wrong in a war zone. Back in 2010, the US announced it had discovered $1 trillion of untapped mineral deposits in Afghanistan, including some crucial for electric-car batteries, like lithium. The Pentagon went as far as describing Afghanistan as “the Saudi Arabia of lithium.”

All very important stuff, the kind of geo-economic shock that redraws the global political map. But it was, as many said then, and as everyone knows now, a complete fantasy. The same applies to Ukraine’s alleged riches.

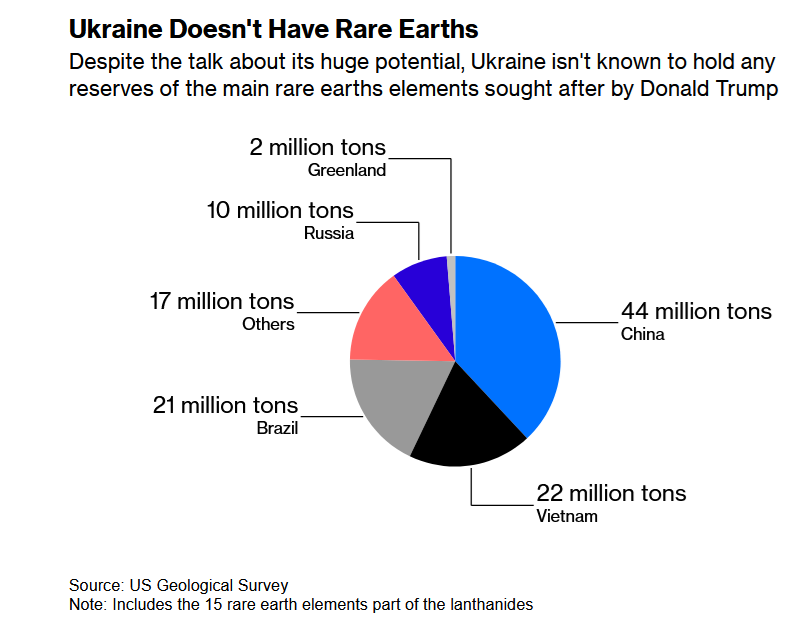

If the focus in Afghanistan was largely copper and lithium, key to the electrification of everything, the spotlight in Ukraine is on rare earths, a collection of 17 elements that high school chemistry students would remember for their tongue-twisting names. The list includes the likes of praseodymium, dysprosium and promethium.

For Trump, the importance of rare-earth reserves comes from the fact that China dominates global supply. In tiny amounts, the elements are used in exotic alloys. Though often presented as essential to high-tech applications and weapons production, their uses are far more prosaic. Dyson Ltd., a popular British maker of home appliances, boasts that it uses the element neodymium in the magnets of its vacuum cleaners, for example, so they “spin up to five times faster than a Formula One engine.”

The hype about the Ukrainian rare earths began with Ukrainians themselves. Desperate to find a way to engage Trump, they miscalculated presenting the then-incoming president a “victory plan” in November that talked up — way, way up — the potential of the country’s mineral resources. Soon, they lost control of the narrative.

On Feb. 3, Trump emphatically said the Ukrainians had “very valuable rare earths.” Always keen to be perceived as a dealmaker, he added: “We’re looking to do a deal with Ukraine where they’re going to secure what we’re giving them with their rare earths and other things.” He doubled down a few days later, telling Fox News on Feb. 11 about his talks with Ukrainian officials: “I told them that I want the equivalent like $500 billion worth of rare earth.”

I was puzzled. To the best of my knowledge, Ukraine has no significant rare-earth deposits other than small scandium mines. The US Geological Survey, an authority on the matter, doesn’t list the country as holding any reserves. Neither does any other database commonly used in the mining business.

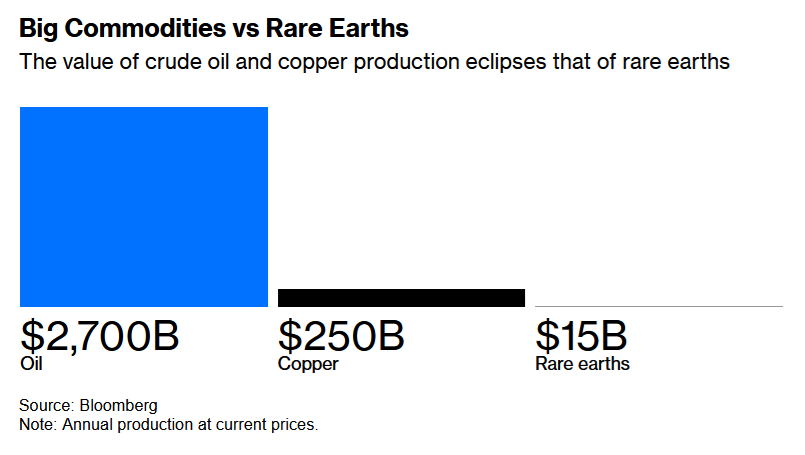

Simply put, “follow the money” doesn’t work here. At best, the value of all the world’s rare-earth production rounds to $15 billion a year — emphasis on “a year.” That’s equal to the value of just two days of global oil output. Even if Ukraine had gigantic deposits, they wouldn’t be that valuable in geo-economic terms.

Say that Ukraine was able, as if by magic, to produce 20% of the world’s rare earths. That would equal to about $3 billion annually. To reach the $500 billion mooted by Trump, the US would need to secure 150-plus years of Ukrainian output. Pure nonsense.1

I see two possibilities: that Trump is right — and I’m very wrong — and Ukraine has, in fact, lots of rare earths; or that he misspoke, and rather than “rare earths” he meant other minerals. Or perhaps he took the small potential of a single element — scandium2 — and extrapolated.

Let’s explore the second option, because at least it would make some sense. While Ukraine doesn’t have commercial rare-earth deposits, it does have mines housing other minerals. Before its war with Russia, Ukraine produced significant amounts of iron ore and coal. Neither are strategic, but the country had been making decent money from both. Problem? Some mines lie now in territory conquered by Russia.

Maybe Trump conflated “rare earths” with the much broader concept of “critical minerals.” Of the latter, Ukraine has some commercial mines of titanium and gallium. Both are fairly valuable and have some strategic importance, but then again, controlling either wouldn’t alter geo-economics. And they certainly aren’t worth Trump’s expressed $500 billion.

Still, the American president steadfastly referred to rare earths; not once, but several times. So then, perhaps he knows something the commodity world doesn’t. But I found no credible source that says Ukraine is brimming with reserves.

Every document someone has pointed out to me regurgitates the same conspiracy-theory claims found on the blogosphere. They tend to mistake accumulations of some rare-earth-bearing minerals as equating with a commercial mine. Many highlight the Novopoltavske deposit, discovered by the Soviets in 1970, as a potential source. While tiny amounts of rare earths are present there, digging them out seems impossible — hence why the site remains an unproductive deposit rather than a mine more than 50 years after its discovery. The Ukrainian government has described Novopoltavske as “relatively difficult” to mine and said that any rare-earth yield would be “off balance,” meaning that it’s not economical to exploit them at current prices. Worse, the mineralogy goes against it: The host source is a mineral that makes extracting the elements very hard.

The worst of the pamphlets claiming Ukraine has a rare-earths cache bears the North Atlantic Treaty Organization imprint and has been widely shared as the “Trump-is-right” proof. It was produced in December 2024 by the NATO Energy Security Centre of Excellence, based in Lithuania. Although affiliated with the military alliance, bearing its name and logo, the entity and its counterparts are autonomous bodies outside the command chain. The document is provocative: “Ukraine emerges as a key potential supplier of rare earth metals such as titanium, lithium, beryllium, manganese, gallium, uranium…” The list should ring every alarm. Anyone with a passing knowledge of chemistry knows none of those minerals are rare earths.

Why NATO’s imprint is attached to the report, which appears devoid of basic fact-checking, is beyond comprehension. A spokesperson told me the views reflected those of the author rather than NATO — something the document doesn’t say. The report, uncorrected, is still available online.

If that’s the source Trump’s advisers used to convince him of Ukraine’s rare-earth riches, it would be depressing — global politics based on copy and paste. It would suit the Kafkaesque year of 2025 well.